If you treat the global economy as a computer, it has a massive bottleneck. It isn’t a lack of processing power, a silicon shortage, or an energy crisis. It is a software compatibility issue running in the minds of millions of ten-year-olds.

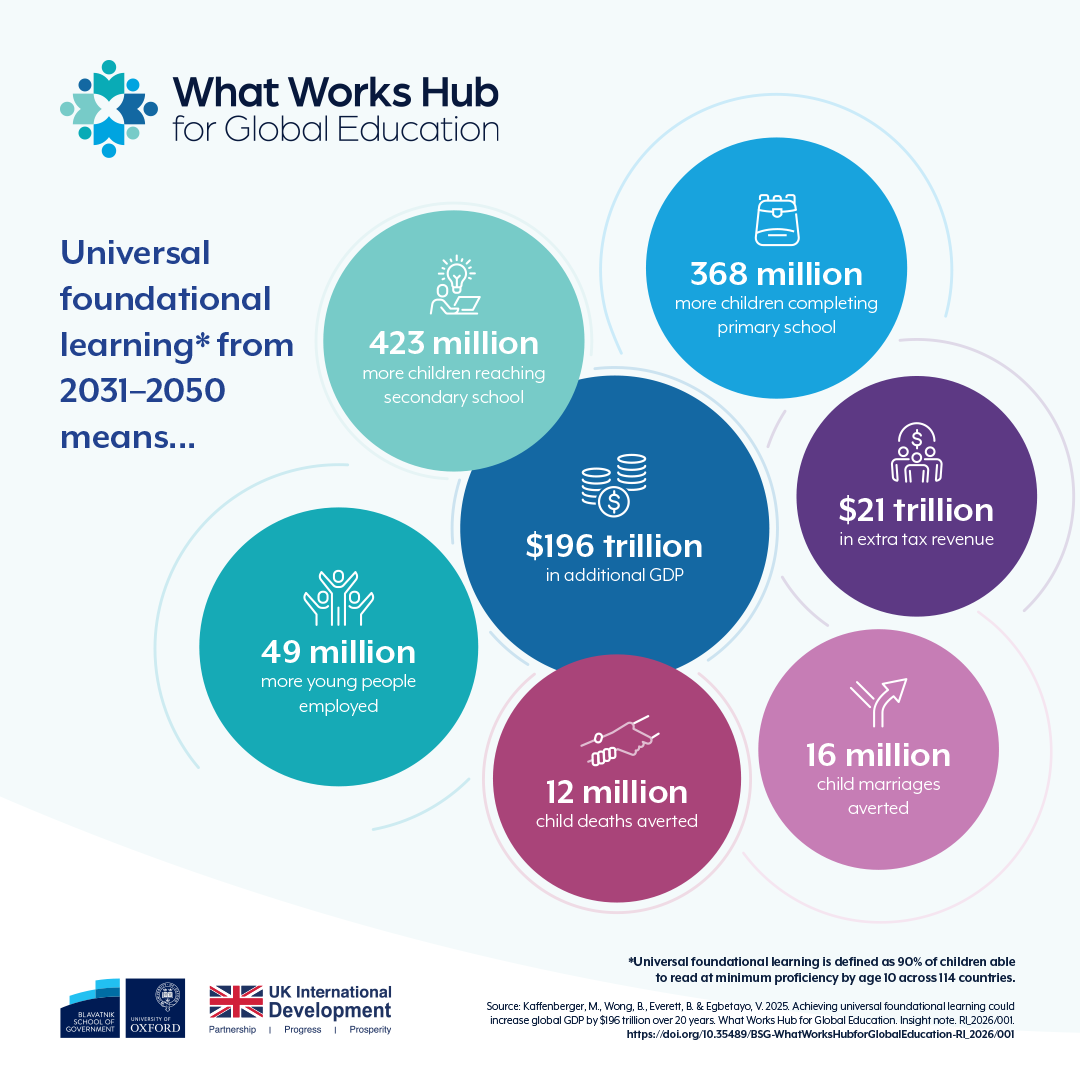

A groundbreaking new analysis released today by the What Works Hub for Global Education (WWHGE), Mettalytics, and the Gates Foundation suggests that fixing this bug—specifically, ensuring 90% of children in low- and middle-income countries can read by age 10—would trigger an economic overclock worth $196 trillion (approx. KES 2.5 quadrillion) over the next two decades.

To put that number in perspective: that is more than double the current global GDP.

The report, titled Achieving Universal Foundational Learning, is the first comprehensive attempt to model the “ROI of reading” across 114 countries. The findings suggest that foundational literacy acts less like a school subject and more like an operating system. When it fails to load by age 10, the user is locked out of the complex applications—secondary school, specialised employment, and health management—that drive a modern economy.

The $196 Trillion Glitch

The core metric here is “Learning Poverty”—a World Bank definition for children who cannot read and understand a simple text by age 10.

Currently, the failure rate is staggering. In low-income countries, only roughly 10% of children can read proficiently. The analysis models a scenario where that flips: what if we hit 90% proficiency (Universal Foundational Learning) starting now, and tracked the results from 2031 to 2050?

The economic projection is startling:

- $196 trillion in additional economic output.

- GDP per capita rising by 27% globally.

- $21.4 trillion in extra tax revenue for governments.

This isn’t just about kids getting better grades. It is about the “compound interest” of cognitive skills. The study relies on data showing that cognitive skills (literally, the ability to process information) are a much tighter predictor of economic growth than just “years spent in a classroom”.

“This research fundamentally reframes foundational learning from an education issue to an economic imperative… When children learn to read, entire economies transform.” — Michelle Kaffenberger, University of Oxford.

The Human Hardware Update

While the GDP numbers grab the headlines, the report’s most compelling data is in the “human hardware” updates—the social glitches that literacy patches.

The model predicts that achieving universal literacy would avert 12 million child deaths between 2031 and 2050. The mechanism here is well-documented but often overlooked: literate mothers are significantly better at interpreting health information, administering medicine, and navigating healthcare systems.

Simultaneously, the data projects 16 million fewer child marriages. The logic follows a “pipeline effect.” If a girl can read, she is less likely to drop out of primary school. If she finishes primary, she is more likely to enter secondary school. As education duration increases, the probability of early marriage plummets.

Regional Spotlights: The Kenya Context

For readers in Nairobi, the data hits close to home. The report highlights Kenya specifically, noting that currently, only 21% of 10-year-olds are reading proficiently.

If Kenya were to bridge this gap and reach the 90% target, the economic model predicts a 68% increase in GDP per capita by 2050.

In absolute terms, that is an additional $2 trillion (approx. KES 260 trillion) in economic output for Kenya over the 20-year period. This revenue isn’t just abstract wealth; it translates to government fiscal space. The report estimates globally that the tax revenue generated ($21 trillion) would provide the necessary budget for infrastructure and climate resilience.

Other notable country-specific projections:

- Nigeria: Could avert 3.3 million child deaths and see 42 million more children complete primary school.

- India: Stands to gain $38 trillion in economic output, with GDP per capita rising by 47%.

- Vietnam: Despite already having high literacy (82%), reaching the last 10% would still yield $738 billion in gains.

The Employment Crisis

We talk frequently about the “skills mismatch” in the tech sector—graduates who can’t code. But this report highlights a more fundamental mismatch: a global workforce that can’t read instructions.

The analysis suggests that universal literacy would result in 49 million more young people in persistent, steady employment. The logic is that literacy is the gateway to “trainability.” Without it, vocational training, digital upskilling, and higher education are functionally impossible to access.

In Sub-Saharan Africa alone, this translates to 22 million additional employed youth, directly attacking the region’s massive youth unemployment crisis.

The Implementation: How do we execute the code?

The report insists this isn’t a fantasy. We know how to teach reading. The authors point to “structured pedagogy” (a highly organised, evidence-based method of teaching) and “Teaching at the Right Level” (grouping kids by ability rather than age) as proven, scalable patches.

Dr. Ben Piper of the Gates Foundation notes that Generative AI is now offering “unique opportunities” to enhance these proven approaches, potentially lowering the barrier to entry for teachers in under-resourced classrooms.

Final Take

It is easy to get lost in the trillions. But the critical takeaway here is the inefficiency of the current system. We are currently trying to run a 21st-century global economy on a population where, in many regions, 90% of the new “users” (children) cannot process basic data (text).

If this were a server farm running at 10% efficiency, we’d scrap it and rebuild it overnight. This report suggests that the cost of not fixing global literacy is roughly $196 trillion. In the cold calculus of economics, ignoring foundational learning isn’t just a tragedy; it’s bad business.