On February 19, 2026, the wood-panelled courtroom at Milimani Law Courts delivered more than an acquittal. It delivered a warning.

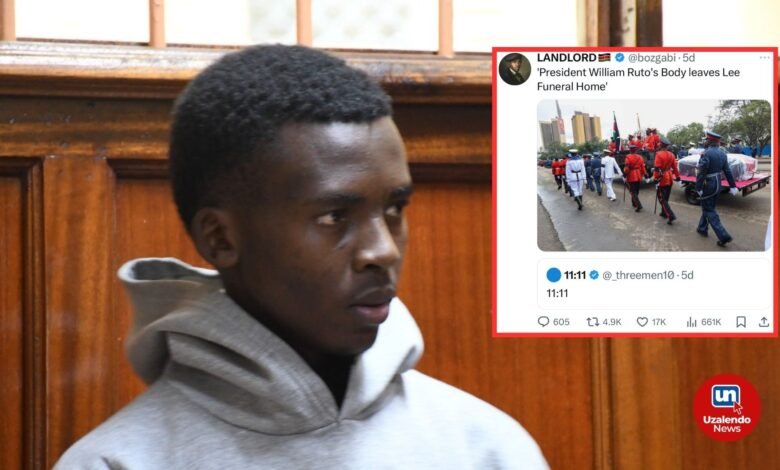

Principal Magistrate Caroline Nyaguthi cleared Moi University student David Oaga Mokaya of charges under the Computer Misuse and Cybercrimes Act (CMCA), after prosecutors failed to prove that he authored or published a social-media post implying the death of President William Ruto. The ruling underscored a growing judicial impatience with weak digital attribution, questionable data-collection practices, and expansive interpretations of cybercrime law.

The Attribution Problem

At the heart of the case was a familiar digital-forensics dilemma: device access does not equal authorship.

A forensic analyst testified that 1.2GB of data was extracted from Mokaya’s Samsung smartphone using Cellebrite tools. The extracted data linked the device to the social-media account in question. But under cross-examination, the prosecution’s own witness conceded that the analysis could not scientifically prove that Mokaya himself authored or published the offending post.

Also Read: A new forensic report reveals how Israeli tech is fueling DCI’s crackdown on political dissent

The defence argued that alternative possibilities — including third-party access, credential compromise, or remote interaction — could not be ruled out. The court agreed that the evidentiary chain left reasonable doubt.

That finding is significant. Kenyan cybercrime prosecutions have often relied heavily on device possession and subscriber records. This judgment reinforces a higher threshold: proving that content passed through a device is not the same as proving who composed it.

Telco Data and Due Process

Another contentious issue concerned how investigators obtained subscriber data and location records. Court reporting and civil-society statements indicate that Safaricom provided call-data and related information to investigators through an administrative request rather than a judicial warrant.

Safaricom PLC has previously stated that it cooperates with law-enforcement agencies within the law. However, privacy advocates argue that reliance on administrative letters risks sidestepping safeguards embedded in the Data Protection Act and constitutional privacy protections.

While the acquittal ultimately rested on insufficient attribution evidence, the case has renewed scrutiny of how telecom operators respond to police requests and whether judicial oversight is consistently applied.

A Pattern of Expansive Application

Mokaya’s case does not stand alone. Over the past four years, several prosecutions under the CMCA have sparked debate about the law’s breadth and its potential chilling effect on digital expression.

In 2025, civic technologist Rose Njeri Tunguru was charged under Section 16 of the CMCA for “unauthorised interference” after building an automated tool that enabled citizens to email Members of Parliament about the Finance Bill. Prosecutors characterised the high-volume automated messaging as akin to a distributed denial-of-service attack. A court later dismissed the charges, citing defects and insufficient grounding.

Earlier cases — including proceedings against activist Edwin Mutemi wa Kiama over COVID-19 loan infographics — and arrests linked to the July 2025 Saba Saba protests further intensified debate about whether cybercrime provisions are being stretched to address political speech.

The state maintains that the CMCA is a necessary tool against misinformation, fraud, and digital sabotage. Critics counter that vague drafting and broad enforcement discretion create space for overreach.

The 2025 Amendments

Concerns deepened after Parliament enacted the Computer Misuse and Cybercrimes (Amendment) Act, 2025. Among other changes, the amendments clarified and expanded the definition of “access” to include entry through programs or automated tools.

Government officials framed the reform as essential to combating bot-driven fraud and cyber-attacks. Civil-society organisations warned that poorly defined automation language could expose legitimate developers, researchers, and civic technologists to criminal liability.

The Mokaya acquittal does not invalidate those amendments. But it signals that courts may demand tighter evidentiary standards when prosecutors rely on technical inferences.

Judicial Guardrails in a Digital Age

What makes this case consequential is not simply that charges collapsed, but why.

The court did not endorse the underlying post. It did not question the state’s authority to prosecute genuine cybercrime. Instead, it insisted on basic principles: proof beyond reasonable doubt, credible forensic linkage, and lawful evidence collection.

For Kenya’s fast-growing tech ecosystem, the “Silicon Savannah”, that distinction matters. Developers and digital entrepreneurs operate in an environment where automation, scraping, bulk messaging, and API-driven tools are commonplace. If courts equate technical capability with malicious intent, innovation could suffer. If courts require rigorous proof and clear statutory interpretation, a balance may yet be struck.

The acquittal of David Oaga Mokaya therefore represents neither the dismantling of Kenya’s cybercrime framework nor proof of systematic repression. It is, however, a judicial reminder that digital prosecutions must meet the same constitutional thresholds as analogue ones.

As enforcement agencies adapt to online speech and digital activism, the burden will remain on investigators to prove not only that a device was involved — but that a person, acting with criminal intent, committed the offence. In that insistence on precision, Kenya’s courts may be quietly shaping the contours of digital liberty in the republic’s second internet decade.