Spiro Kenya’s electric motorbikes were once marketed as a lifeline for boda boda riders squeezed by high fuel prices. By mid-December 2025, however, the company found itself at the centre of one of Kenya’s most intense tech-and-labour backlashes, with riders accusing it of exploitation, overreach, and “digital slavery.”

What began as one rider’s complaint quickly escalated into a nationwide reckoning over ownership, control, and who really benefits from Kenya’s electric mobility push.

How the controversy started

The storm was sparked by viral posts from @IAMRAPCHA (Rapcha The Sayantist), a Spiro rider who shared images and videos alleging that Spiro:

- Remotely disabled electric bikes

- Marked batteries as “stolen” after five days of inactivity

- Grounded bikes even when inactivity was caused by illness, breakdowns, or repairs

In multiple emotional posts, Rapcha warned other riders:

“SPIRO ARE CRIMINALS!!! Avoid or lose your money!!! I’m a victim!!!”

His posts quickly gained traction, some surpassing thousands of likes and hundreds of reposts, and opened the floodgates for other riders and observers to share similar experiences or draw sharp analogies.

One recurring comparison stuck: “This is like Safaricom disabling your SIM card because you didn’t make calls for five days.”

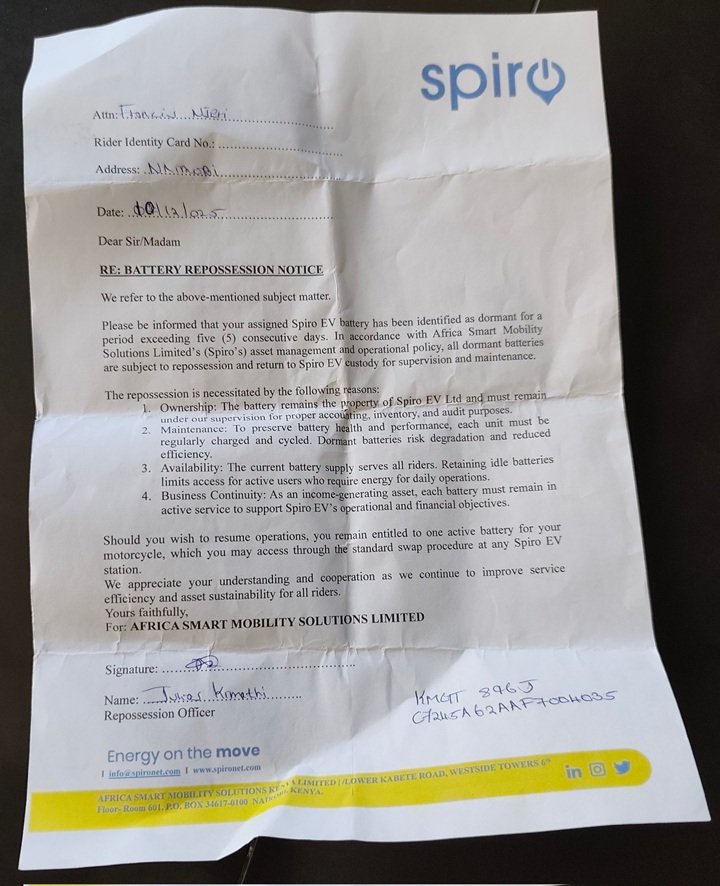

The repossession notice: what it actually says

Central to the outrage was a battery repossession notice issued by Africa Smart Mobility Solutions Limited (Spiro’s legal entity). The letter states that a rider’s assigned EV battery had been identified as “dormant for a period exceeding five (5) consecutive days.”

Under Spiro’s asset management policy, the notice explains, dormant batteries are subject to repossession and return to Spiro EV custody.

The reasons listed are revealing:

- Ownership – The battery remains Spiro’s property and must stay under its supervision.

- Maintenance – Idle batteries risk degradation if not regularly charged and cycled.

- Availability – Idle batteries reduce access for active riders.

- Business continuity – Batteries are income-generating assets that must remain in service.

The letter, shared below, reassures riders they are still “entitled to one active battery” via the standard swap process. But only once they resume operations through Spiro’s system.

To riders, however, the tone felt cold and disconnected from reality. A battery deemed “dormant” during hospitalisation, bereavement, or mechanical repair was still treated as an operational risk.

Spiro Kenya responds

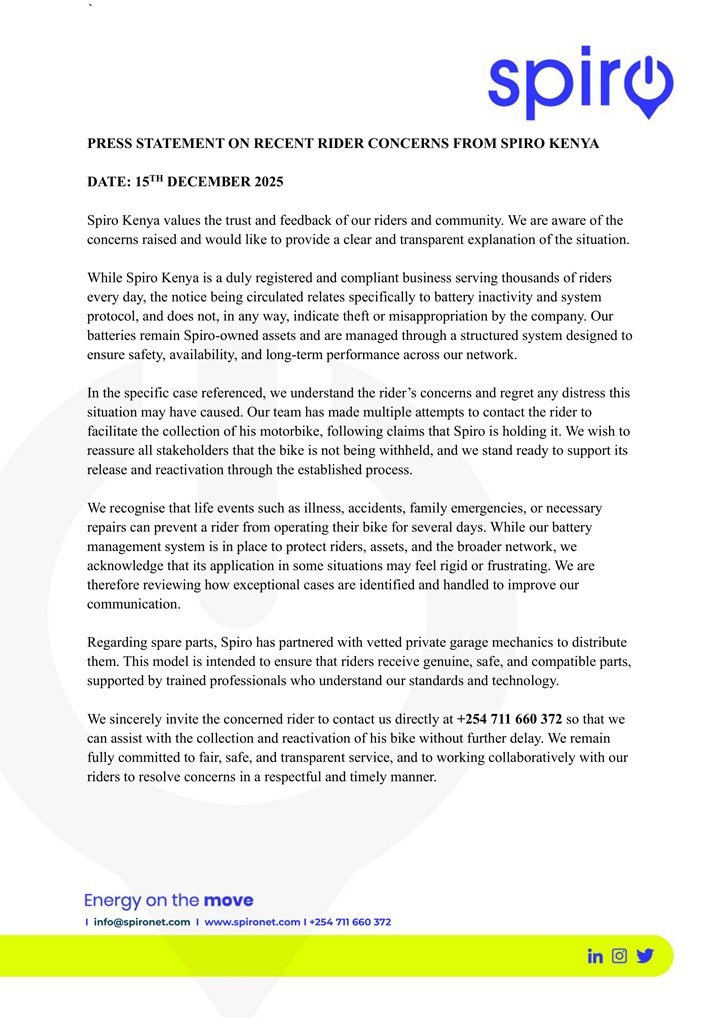

On December 15, Spiro Kenya published an official statement addressing the backlash.

The company emphasized that:

- The circulating notice relates strictly to battery inactivity protocols, not theft

- Batteries remain Spiro-owned assets by design

- The model keeps upfront bike costs low—around KES 95,000, compared to significantly higher prices if batteries were included

- Battery swapping (instead of home charging) is a safety and reliability decision

Crucially, Spiro also acknowledged rider frustration, noting that life events such as illness, accidents, and emergencies can prevent bike use for several days. The company said it is reviewing how exceptional cases are handled, admitting the system may feel “rigid or frustrating” in some situations.

It also denied claims that it was withholding bikes, urging the affected rider to contact Spiro directly for reactivation.

The statement, shared below, was widely seen but poorly received. Replies and quote posts accused the company of dodging the core issue: why disable the entire bike if only the battery belongs to Spiro?

“You don’t really own anything”

That question sits at the heart of the backlash.

Yes, riders pay roughly KES 95,000 for the bike. But without a Spiro battery—non-purchasable, non-chargeable at home, and swappable only at Spiro stations—the bike is effectively unusable.

"It’s like buying a car without a fuel tank, then being told you can only refuel at one company’s stations—and they can shut you down remotely."

In a widely shared thread, @omondike_ described the system as “modern-day bondage”, arguing that riders are locked into a tightly controlled ecosystem where pricing, parts, repairs, and even movement are dictated by one company. The post has gained close to 130K views, over 1,500 likes and 700 reposts, helping push the story beyond tech circles into mainstream discourse.

Monopoly fears and spare parts frustration

Battery control isn’t the only issue riders raised.

Spiro’s statement confirms that spare parts are distributed through vetted private garage mechanics, a move the company says ensures safety and compatibility. Riders, however, describe something closer to a monopoly.

Common complaints include:

- Spare parts priced many times higher than equivalent ICE bike components

- No freedom to repair bikes independently

- Bikes requiring towing—sometimes long distances—if disabled or flagged

To struggling boda boda riders, many of whom operate on razor-thin margins, these constraints feel less like innovation and more like dependency.

However, the December backlash didn’t emerge in a vacuum. In November 2023, riders in Mombasa told Citizen TV that Spiro bikes suffered from:

- Slow battery swaps

- Frequent breakdowns

- Limited swap stations

- Poor customer support

Some said the bikes struggled on steep terrain or longer routes, leaving them parked more than ridden. The perception that Spiro was aggressively scaling while ignoring operational pain points has only hardened since.

There’s also historical baggage. In July 2024, whistleblower Nelson Amenya alleged that Spiro benefited from a controversial tax arrangement involving government officials, claims Spiro has not publicly addressed in detail, but which resurfaced during the current outrage as trust eroded.

To be fair, Spiro’s model isn’t unusual globally. Battery-as-a-service lowers upfront costs, manages degradation centrally, and enables faster energy replenishment than home charging. For many riders, it did make electric bikes accessible.

But Kenya’s boda boda economy runs on informality, flexibility, and human unpredictability. Systems designed around perfect uptime and constant cycling clash with lives shaped by illness, funerals, rain, and breakdowns.

When technology designed to “optimize assets” begins to discipline people, backlash is inevitable.

Where does this leave Spiro and riders?

As of December 16, sentiment remains overwhelmingly negative despite Spiro Kenya’s PR efforts with hired influencers tasked with cleaning up the airwaves. Calls for regulatory scrutiny, lawsuits, and boycotts continue. Some riders still defend the model, arguing no other electric bike comes close to Spiro’s price—but their voices are largely drowned out.

Spiro Kenya says it is reviewing how exceptions are handled. Whether that review translates into meaningful policy changes or is simply a PR pressure valve remains to be seen.

What is clear is that Kenya’s EV future cannot be built on innovation alone. Trust, transparency, and dignity for riders are not optional features. If e-mobility is going to work in Kenya, it needs to offer more freedom than petrol bikes, not less. Right now, Spiro looks less like a green energy saviour and more like a digitally-enforced loan shark.

Do you own a Spiro bike? Have you faced the 5-day lockout? Slide into the comment section with your experiences.