For months, the status of Rich Communication Services (RCS) in Kenya and several other countries has been a frustrating mystery, leaving users in a digital no-man’s-land. The next-generation messaging protocol, which brings WhatsApp-like features to the default SMS app, has been functionally absent for many Safaricom and other carrier subscribers since August.

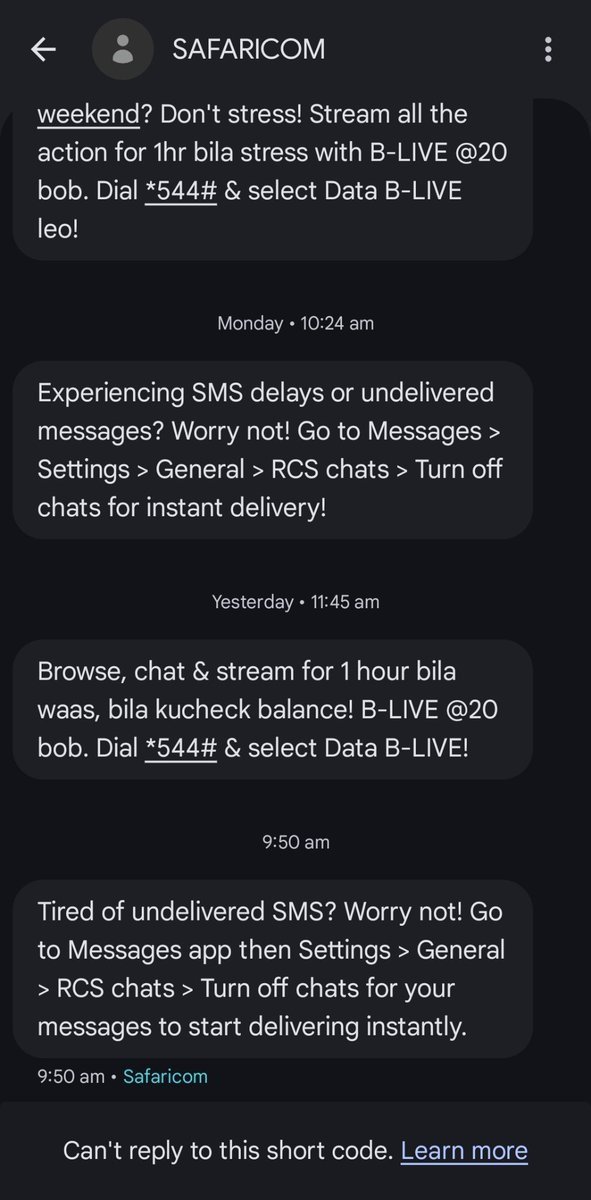

While the issue has been a frustrating ‘he said, she said’ between Google (insisting it’s a carrier problem) and Safaricom support (insisting it’s a Google problem), the operator has now provided the clearest indication yet of where it stands. Safaricom has begun sending out direct SMS messages to users, not offering a fix for the RCS outage, but rather encouraging them to turn the feature off entirely.

The message advises users experiencing issues with delayed or undelivered messages to take a drastic step: Go to Messages app then Settings > General > RCS chats > Turn off chats for your messages to start delivering instantly.

Ostensibly, this is a customer service message to improve the experience, but the implication is clear: RCS is the problem, and disabling it is the solution. While Google still insists that availability of RCS varies by region and carrier for Safaricom users, this is effectively an operator-issued directive to abandon Google’s protocol that was working just fine until recently in favour of the good old, paid-for Short Message Service (SMS). And the fact that Google says if you get the message “Not supported – RCS chats are not supported by your carrier” means RCS isn’t currently supported by your carrier only adds to the speculation that Safaricom and other carriers have effectively disabled RCS support despite their continued insistence that it’s Google’s fault.

The elephant in the room: SMS revenue

The sudden disappearance of RCS has been widely speculated to be linked to a potential pull-back of Google’s Jibe service. Jibe is the backend system Google uses to provide RCS where local carriers have not yet deployed their own infrastructure. If Google has indeed stopped providing this “fallback” service, the onus falls squarely on local operators like Safaricom and Airtel to deploy their own RCS support.

This is where the financial incentive, or lack thereof, enters the picture. Why would a carrier spend money to implement a service that directly cannibalises one of its existing, profitable revenue streams?

Safaricom’s own financial statements provide compelling evidence for this argument. Safaricom Ethiopia, in its latest financial statement for the year ending March 2025, made it abundantly clear that messaging is a core part of its strategy. Messaging revenue there closed the year at KES 82.0 million, growing a massive 93.9% year-on-year (YoY). Furthermore, the company explicitly stated: “We understand that strategically, beyond mobile data, we need to be a fully-fledged telco which has voice, SMS and mobile money revenues…”

With customers sending messages at a retail price of KES 1.20 per SMS, this is a clear, high-margin revenue source that RCS, which replaces SMS with a data-based chat service, would immediately threaten.

While Safaricom Kenya does not disclose a specific standalone SMS revenue figure, it is included under the expansive umbrella of “Other services revenues” alongside the dodgy Okoa Jahazi access fee, which hit a total of KES 7.86 billion and grew 5.3% YoY. Crucially, the report also noted that Mobile Incoming revenue declined 4.8% YoY. In a climate where voice revenues are under pressure, the mobile operator is even less likely to risk supporting a feature that could further erode another traditional revenue stream like SMS.

If the Jibe pullback theory is accurate, it means Google’s RCS backbone was withdrawn, leaving carriers like Safaricom to either adopt their own RCS systems or abandon support. And in markets like Kenya where WhatsApp dominates messaging and SMS remains a paid product, carriers may simply choose not to bother.

The timing of Safaricom’s RCS disablement message, months after the global outage began, suggests a quiet acknowledgment that RCS is unlikely to return anytime soon for Kenyan users. Until a regulatory body or a major market shift forces their hand, it is highly likely that Safaricom, and other regional carriers reading from the same playbook, will continue to defer fixing the RCS crisis, preferring instead to keep the SMS revenue stream flowing.

The message to disable RCS is effectively the company’s unofficial policy on the matter.